Dear Dad,

I miss you, Dad, but it took a beautiful young woman whom I have never met to help me realize just how much. I don’t know her name but still, I consider her a friend. I call her JD (short for Jane Doe which is the way she signed a personal email to me once a while back), and she has a blog called “BeautyBeyondBones” which chronicles her journey out of anorexia, a journey that began at a point when the evil that is anorexia had very nearly claimed her life and surely must have made her Father think his own life wasn’t worth living if he couldn’t help his little girl. I was inspired to write this letter by a recent post on her blog titled “To My Father.”

I am 62 years old and it has been 44 years since your alcoholism took you from us. When you got me a job working on one of your survey crews building part of the Southern Tier Expressway near Olean, NY when I was 17, I used to wake up in the morning and look out the door of my bedroom in the little farmhouse we rented and lived in during the week, and I would see you just waking up yourself, standing in front of the refrigerator and – without ever closing the refrigerator door – you would chug your first (but far from your last) beer of the day. The others would be interspersed with quick shots of whiskey in local bars when you took your ‘breaks.’

I watched in silent puzzlement, incapable of understanding what makes someone do that, and I remember thinking to myself, “I will never be like that.”

Then a funny thing happened on my own journey to manhood: I became just like that.

It would take decades and a nearly successful suicide attempt for me to finally examine the causes of our addictions, and while we were very different people living in very different worlds, the trigger that sent the bullet of self-destruction careening towards the heart of our lives was: pain.

It’s funny, though, because you had provided me with the answer in a conversation we had before you died, but it would be a conversation that went unheard – and was not understood – until after I read a book in the same hotel room in which I nearly ended my own life.

No, it wasn’t the Bible. Discovering the beauty of those particular words would not come until later, after I had gone to prison.

No, the book I am referring to is “The Greatest Generation” by Tom Brokaw. I had picked it up off the shelf of Mom’s house after she and Roland had passed away, and it stayed on my shelf until I was suddenly faced with the ruination I had wrought upon my life and had the time to read it because, well, pretty much because it was there and I had a lot of time on my hands in those days leading up to my incarceration.

In that book I read stories about men who had fought in World War II. Stories most of them had never told before, and in many cases were revealed to have been responsible for their own alcoholism. Their stories reminded me of the one you told as I approached my 18th birthday in Dunkirk, NY near the end of the Vietnam War. I remember that conversation because it was the only serious, revealing conversation we ever had together.

John and Jim (my brothers) had joined the Air Force and the time when I would be eligible for the draft was rapidly approaching. Because of my ‘mischievous’ nature and the scrapes with the law I had made you all suffer through with me, I think you knew my only option would be the draft, the Army, and the face-to-face jungle fighting I would encounter.

I vividly remember you telling me that if I did not want to go fight this war, you would understand and you would “spend every penny this family has” to keep me at home.

And then you told me why.

Lying on the bed in my motel room reading about other fathers’ wartime experiences in Brokaw’s book, I recalled that conversation. You had been drinking, but then, by that time there was rarely a moment when you weren’t, and your eyes seemed to lose a little focus as you drifted back in time and began to recount your experiences:

You were a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army and you were in command of machine-gun crews on an island in the South Pacific. The Japanese would break the stillness and charge your positions with blood-curdling screams and yells and they would come at you in wave after wave of living, breathing, humanity. Husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, uncles, nephews, grandsons.

One and all they would come after you with the intent of killing you and everyone in your command.

Being in command, you were responsible for giving the order to fire. Your men would obey, and they would cut down hundreds of living, breathing men (boys, really) who took their last breath on earth because you had ordered it. You would watch them fall, you would hear their cries, and you would smell the smoke, the blood, and the fear, and when it was over, you would see the carnage wrought by the command you had given.

Suddenly I had my answer. I knew why you stood in front of the refrigerator, replacing orange juice with beer.

Pain.

You were trying to deaden the pain that racked your body because of the horrors of war and the execution of your responsibilities as a soldier. You were trying to wash away the images that would not go away. You were dealing with your tormented soul in the only way you knew how.

And at that moment I realized that I, too, had done the same thing. The pain in my life was certainly not the same as yours, but it had the same life-controlling effect. Not knowing how to deal with it, or what to do with it, I tried to deaden it and to wash it away, but in the end, it was always right there waiting for me. And in the end, it helped me to succumb to temptation and be seduced by evil.

Fortunately for me, as I lay dying on the floor of the shower that was just steps away from where this realization was finally hitting home, my eyes were opened to the answer: Although you didn’t want to sacrifice me to the horrors of war, God did sacrifice His Son so that we all can lay down our burdens of pain at the foot of the Cross on which He died.

I am sorry we didn’t have more time together, but you gave me much that I use on a daily basis now that I have stopped ‘standing in front of the refrigerator.’ Your intelligence, your work ethic, your sense of humor, and your integrity have all come to the surface now that I have stopped trying to destroy myself to escape my own pain.

I do miss you very much, Dad, and I love you. I wish I had realized just how much and had been able to tell you before you died. Thanks for your service to this country. It was service that cost you your life, even if you were not killed on the battlefield. Your pain kept you from being all that you could have been as a father, but I cannot hold that against you since my own pain did the same to me.

I hope I have become a Son you can be proud of, and if I have it is because you are my Dad, and because I have found a new refrigerator to stand in front of, and it looks like this:

Happy Father’s Day, Dad.

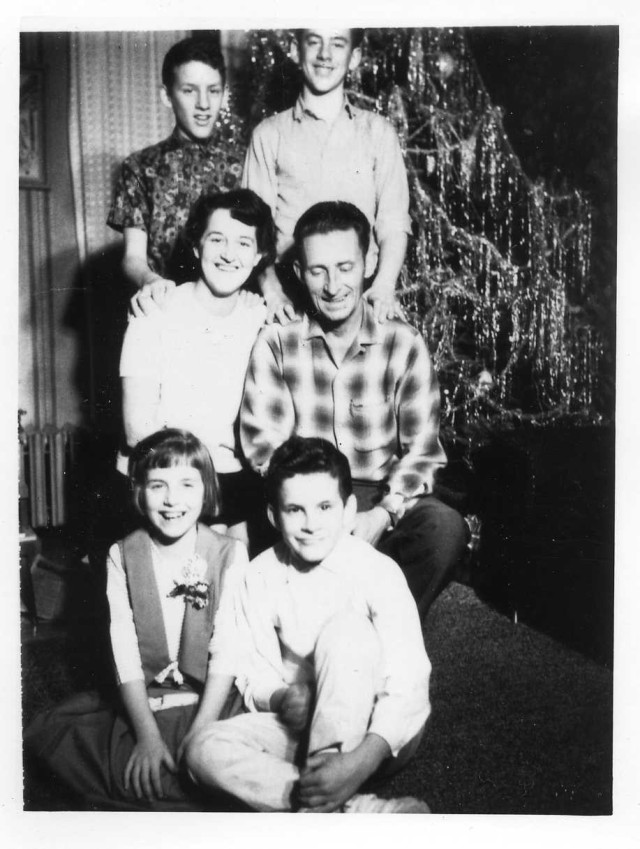

That’s my Dad, looking at me. I think he knows how much trouble I am headed for.

Beautiful Tony 🙂

LikeLike

You’re referring to my picture, right? 😉

Thanks, Diane. Your support, and comments, are much appreciated, my friend!

LikeLike